One of the gratifying things about writing this blog is the collective power of Mystery Pollster readers. Last week, I emailed some questions to Zogby International about the methodology they used for a recent poll conducted on behalf of the online gambling industry. The poll had been the subject of a column by Carl Bialik for the Wall Street Journal Online, something I discussed in a post last Friday. Zogby’s spokesman ignored my emails. However, over the weekend MP reader Ken Alper reported in a comment that he had been a respondent to the Zogby gambling poll. He also confirmed my hunch: Zogby conducted the survey online. That fact raises even more questions about the potential for bias in the Zogby results.

Why is it important that the survey was conducted online?

1) This survey is not based on a “scientific” random sample — The press release posted on the web site of the trade group that paid for the poll makes the claim that it is a “scientific poll” of “likely voters.” As we have discussed here previously, we use the term scientific to describe a poll based on a random probability sample, one in which all members of a population (in this case, all likely voters) have an equal or known chance of being selected at random.

In this case only individuals that had previously joined the Zogby panel of potential respondents had that opportunity. As this article on the Zogby’s web site explains, their online samples are selected from “a database of individuals who have registered to take part in online polls through solicitations on the company’s Web site, as well as other Web sites that span the political spectrum.” In other words, most of the members of the panel saw a banner ad on a web site and volunteered to participate. You can volunteer too – just use this link.

Zogby claims that “many individuals who have participated in Zogby’s telephone surveys also have submitted e-mail addresses so they may take part in online polls.” Such recruitment might help make Zogby’s panel a bit more representative, but it certainly does not transorm it into a random sample. Moreover, he tells us nothing about the percentage of such recruits in his panel or the percentage of telephone respondents that typically submit email addresses. Despite Zogby’s bluster, this claim does not come close to making his “database” a projective random sample of the U.S. population.

2) The survey falsely claims to have a “margin of error” — Specifically, the gambling survey press release reports a margin of error 0.6 percentage points. That happens to be exactly the margin you get when you plug the sample size (n=30,054) into the formula for a confidence interval that assumes “simple random sampling.” In other words, to have a “margin of error” the survey has to be based on a random probability sample. But see #1. This is not a random sample.

Several weeks ago, I wrote about an online panel survey conducted on behalf of the American Medical Association that similarly claimed a “margin of error.” But in that case, the pollster quickly corrected the “inadvertent” error when brought to his attention:

We do not, and never intended to, represent [the AMA spring break survey] it as a probability study and in all of our disclosures very clearly identified it as a study using an online panel. We reviewed our methodology statement and noticed an inadvertent declaration of sampling error.

I emailed Zogby spokesman Fritz Wenzel last Thursday to ask how they justified the term “scientific” and the claim of a “margin of error.” I have not yet received any response.

3) The survey press release fails to disclose that it was conducted online — Check the standards of disclosure of the National Council on Public Polls, standards adhered to by most of the major public pollsters. They specifically require that “all reports of survey findings” include a reference to the “method of obtaining the interviews (in-person, telephone or mail).” Obviously, Zogby’s gambling poll release includes no such reference.

Now, it is certainly possible that the press release in question was authored by the client (the gambling trade group) and not by Zogby International. My email to Fritz Wenzel included this question. The subsequent silence of the Zogby organization on this issue is odd since most pollsters, including my own firm, reserve the right (usually by contract) to publicly correct any misrepresentations of data made by our clients.

4) This online survey concerned the regulation of online activity — Even surveys conducted using random sampling are subject to other kinds of errors. Specifically, when those not covered by the sample or those who do not respond to the survey have systematically different opinions than those included in the survey, the results will be biased. At a minimum, Zogby’s methodology can include only Americans that are online. More important, it does not randomly sample online Americans. Rather, it samples from a “database” of individuals that opted in, many because they saw a banner advertisement on a web page. As such, these individuals are almost by definition among the heaviest and most adventurous of online users.

While MP is intrigued by new methodologies that claim to manipulate the selection or weighting of results from such a sample to resemble the overall population, he warns readers of what should be obvious: The potential for bias using such a technique will be greatest when the survey topic is some aspect of online behavior or the Internet itself. With these topics, the differences between the panel and the population of interest are likely to be greatest.

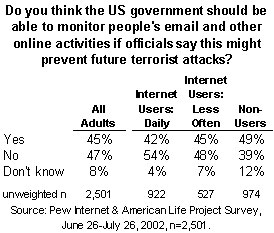

I searched for but could not find a random sample survey that could show the relationship between attitudes on online gambling and time spent online. However, I did find a data on potential government restrictions that allow for such analysis in a survey conducted in the summer of 2002 by the Pew Internet & American Life Project. The survey asked a question about government monitoring of email and also asked respondents how often they went online. A cross-tabulation shows an unsurprising pattern. Those who went online “daily” opposed government monitoring of email by a margin of twelve points (42% yes, 54% no). Those who were offline altogether supported monitoring by ten points (49% yes, 39% no). Heavy online users are more skeptical of government regulation of the Internet than the population as a whole.

Now obviously, we can only speculate whether such a pattern might apply to the regulation of Internet gambling, but common sense suggests that it is a strong possibility. And it provides yet another reason for skepticism about the results of this particular Zogby poll.

So to sum up what we have learned:

In Carl Bialik’s column, American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) President Cliff Zukin described the survey questions as “leading and biased.” Further, the survey release failed to disclose that it was conducted online and made the statistically indefensible claim to be a “scientific poll” with a “margin of error.” The failure to disclose the use of sampling from an online panel is particularly deceptive given that an online activity was the focus of the survey. Add that all up and you get one remarkably misleading poll release.

This story also presents a tough question for Carl Bialik’s editors at the Wall Street Journal Online: Is it statistically defensible to report a “margin of error” for this non-probability sample? And if not, why does the Wall Street Journal Online allow Zogby to routinely report a “margin of error” for the Internet panel surveys that the Journal sponsors?

Highlights from the SCO Blogroll

From Virginia Postrel, a short history lesson on what is and isn’t a “crisis” with regards to gas prices. Doug Williams at Bogus Gold also explains the economics of oil prices for those that think the government must do something….

Wow, Mark. Another impressive summary of what has to be one of the leading problems facing our research industry’s migration to more and more Internet-sampled surveys.

I hate to say it, but I think most decision-makers on the client side have done either one of two things as they continue to press for more web-administered surveys (due to faster turnaround and lower cost):

(1) They understand that an Internet sample isn’t a probability sample, and therefore has no margin of error, but those Internet surveys are so damn fast and cheap — who cares?!

(2) Or, they never really understood margin of error in the first place, so — who cares?!

I am beginning to think that the strongest remaining bastion of marketing research buyers who still respect representative samples and robust response rates are the folks in the social sciences with large amounts of grant money to spend.

Like all things we sacrifice for the bottom line (cheaper outsourced technical support, cheaper gasoline that doesn’t have to pass EPA standards, cheaper 2-gallon jars of pickles that put the manufacturer itself out of business, etc.) — in the end, you get what you pay for.

While I certainly see issues here, I think that the misuse of sampling error and confidence interval terminology isn’t as egregious as you suggest. After all, there isn’t a major real-life poll we can point to where every member of the target population really had an equal chance of being sampled. As you well know, they run up against call screenings, refusals, respondent not being at home, multiple phone lines, lack of a telephone, etc.

As such, if the standard for using confidence intervals is that every member of the population has “an equal or known chance of being selected at random”, then no nationwide poll should be using the terminology.

I am beginning to think that this should indeed be the case. Given that most political polls when taken together seem to have standard deviations 2-3x what one would normally expect from random sampling, I wonder if we need to come up with new language to describe the margin of error in polls that are somewhat “improvisational” when it comes to sampling. They aren’t useless as they do have predictive power, but that predictive power has a larger error term than mere sampling error would indicate.

Remind anyone of the Ohio mail-in poll of the mail-in ballot reform ballot measure?

This is totally OT, but I have a question for you about Rasmussen.

I have checked their postings of Bush JAR regularly for a year or so now, and in the last couple of months I have noted something odd.

Rather than posting the new poll numbers promptly at 12 noon EST,

the daily numbers get posted as much as two days late. This happens most of the time these days. In the past, the new numbers always went up on schedule.

Assuming I’m not just having a browser problem, I wonder if there is something going on. Is Rasmussen cooking their numbers by waiting for a high point in the daily numbers for a cutoff?

Any way you can check this out?

Thanks.

Your complaining about skewed results? I’ve only seen a couple of presidential polls that included more than two candidates. As with any poll ive participated in the answers seem to lean in a certain direction to invoke certain sought after results that would support the pollsters opinions.