In his Washington Post “Media Notes” blog, Howard Kurtz raises an important question about the coverage of the polls showing “new lows” for George Bush (hat tip: Kaus). Kurtz and Kaus are right to wonder if the “new low” headlines give a distorted impression of a continuing day-to-day decline and right to imply that when it comes to covering polls, more references would be better than few.

The question Kurtz asks at the end of this passage is definitely worth considering:

Can I just grumble a little about this USA Today /CNN poll?

“President Bush’s ‘approval rating’ has sunk to a new low according to a USA TODAY/CNN/Gallup poll released Monday.“The latest results show only 36% of those polled saying they ‘approve’ of the way Bush is handling his job. Bush’s previous low was 37%, set last November.

“Sixty percent of those polled said they ‘disapprove’ of Bush’s performance. That matches an all-time worst rating hit last November and again two weeks ago.”

Bush is at a new low compared to USA’s last poll. CBS has Bush at a new low compared to the last CBS poll. Etc., etc. All true, but they give the collective impression that Bush is sinking week to week. Why do they only compar[e] figures to their own past surveys, when they’re fully aware of the others?

One good reason to avoid cross-pollster comparisons is the issue of “house effects.” Some pollsters typically show Bush a little higher than others, some a little lower. These effects are not evidence of intentional “bias,” but rather due to small differences in methodology. Some are obvious (such as the Fox poll interviewing only registered voters) some less so (such as why CBS, Fox and the Pew Research Center seem to get a higher “don’t know” response on the job rating question than other pollsters). See the posts on “house effects” by Charles Franklin and especially Robert Chung.

But the potential for spurious cross-pollster comparisons does not entirely explain why news organizations shy away from references to polls other than their own. They could do what we do here at MP: make apples-to-apples comparisons across a number of different polls.

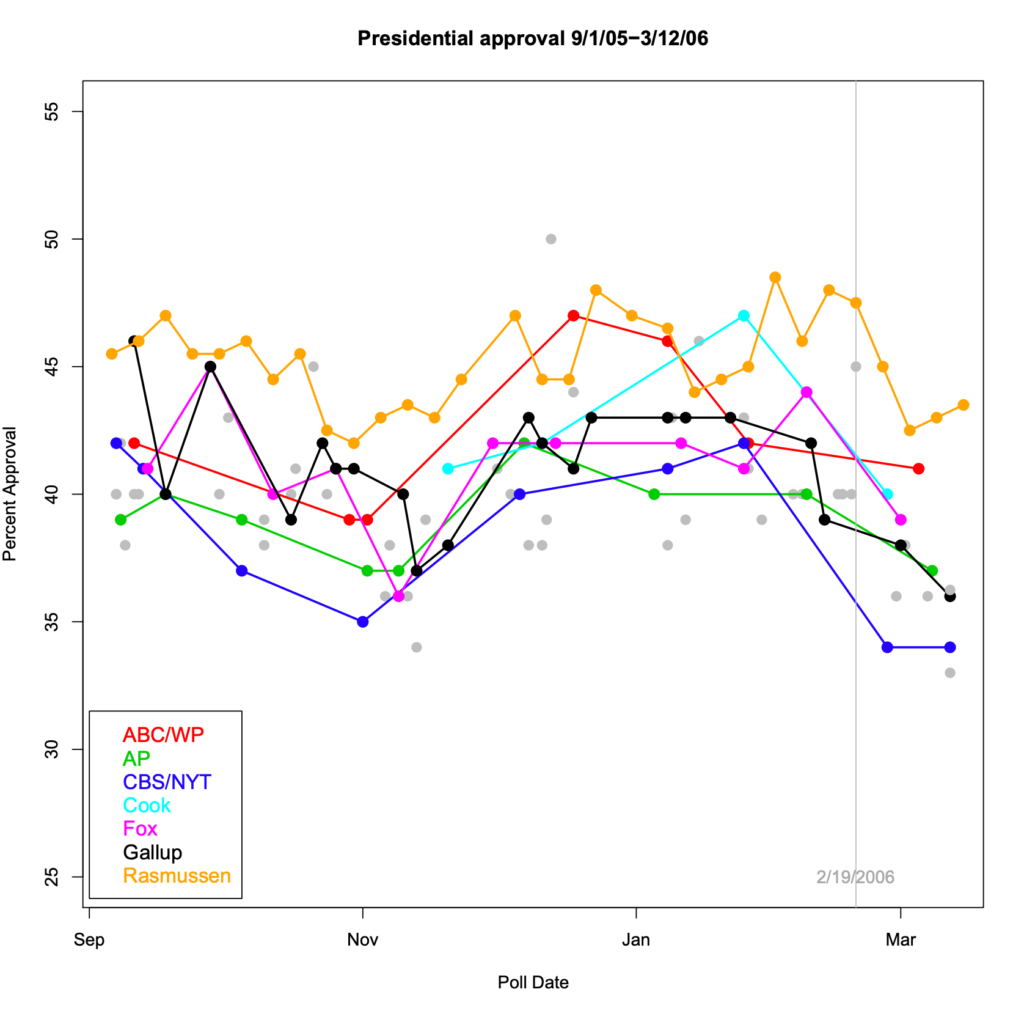

So let’s take a moment and do just that, with an assist with a graphic specially created for MP readers by our friend, Professor Charles (“Political Arithmetik“) Franklin. The chart below [click it for a full size version] shows the overall Bush job approval rating on every national public poll released since Labor Day, with lines plotted for seven pollsters.

Three important points emerge from the chart:

- Every survey released since February 19 (the grey vertical line) shows a decline of at least four percentage points since early January, with every pollster except ABC/Washington Post showing that decline occurring during February.

- The lows of late February roughly match those recorded in later October. Collectively these levels represent the lowest measured during the Bush administration (as confirmed by another graph on Political Arithmetik).

- Over the last three weeks, only Gallup, CBS and automated pollster Rasmussen have fielded more than one survey. None show any statistically significant change since during that time.

Which brings us back to the important part of Kurtz’ question: Why does each intra-pollster comparison herald a new “new low” headline, when the more accurate read (for now) would be to treat each new survey as confirming the same drop since February recorded by all? Such an approach does not require a snazzy graphic like the one above (though it couldn’t hurt). It could be done in a sentence: “Our results are consistent with those last week by …”

Actually, the very article that Kurtz grumbled about included just such a reference:

[The latest Gallup] results closely resemble those reported last week in an Associated Press/Ipsos poll. That survey put Bush’s approval rating at 37% – matching the AP/Ipsos poll’s all-time low.

However, Kurtz is certainly right that such references are rare. I can think of three reasons for that reticence, and all three should give both pollsters and journalists pause.

First, the “new low” headline or lead is a lot more dramatic and easier to write. Most pollsters are guilty of this habit – I know I have done it in internal memos to clients – even when we hasten to add in the next sentence that, well, the new low is only a point or so lower than the old low measured last week, and therefore isn’t statistically significant. But still, it is a new low! This bad habit is a matter of human nature. No pollster wants to report that the latest survey reveals “no significant change.”

Second, news organizations consider it bad form to give prominent play to surveys done by their competitors, even when as Kurtz points out, “they’re fully aware of the others.”

Ironically, in a recent online chat posted elsewhere on WashingtonPost.com, a reader asked Post polling director Richard Morin a similar question:

Albany, N.Y.: Do you believe that the polls done by other news outlets are just as newsworthy as your own poll, and if so, why do they not receive the same degree of prominence in The Post?

Richard Morin: No, frankly, I don’t, and for the same reason that we do not publish stories about the same press conference done by USA Today, Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, that other Times, etc. We run our own. That does not mean we do not cite other poll findings, or that we won’t give strong play to a poll on a topic we haven’t surveyed on. It’s just that we have more confidence and more control over our own polling.

Morin, to his credit, did use the same chat session to compare and contrast the most recent Post/ABC poll results to other recent surveys by Gallup, Diageo/Hotline and CBS/New York Times.

Third, there is the issue of marketing. As Tom Rosentiel put it in his recent POQ article, “Political Polling and the New Media Culture” (2005, 69:5, p. 703), “marketing considerations” drive the way polls are used, “even at major news organizations.” Rosentiel related a fourteen-year-old story about a strategic planning retreat at the Los Angeles Times, in which an unnamed editor discussed the Times poll:

The paper would be conducting this many polls and spending this much, he pointed out, as if to cut off any further discussion on the point, because we needed to recognize something. Polls are a form of marketing for news organizations. Every time a Los Angeles Times poll is referred to in other media, the paper is getting invaluable positive marketing of its name and its credibility. The same was true for any news organization, CBS News, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the rest. So if there was more money devoted to this than the assembled political journalists thought necessary, that was the reason, he was implying, and there was no point in arguing the issue.

None of these issues should preclude reporting that references polls sponsored by multiple news organizations. The marketing considerations should be generally enhanced if more stories made reference to more polls, and even Richard Morin’s misgivings about giving prominent play to other polls obviously did not get in the way of his referencing those polls on WashingtonPost.com. Having said that, I am not sure I agree with his press conference analogy. We certainly would not expect the Washington Post to reprint press conference stories by other newspapers, but in that case the specific underlying facts of the event, the words spoken by the president, are not in question. All reporters work from the same recording or transcript.

Polls are different. They may all attempt to measure the same underlying “public opinion” on the same issues, but the sampling methodologies and question wording used add fuzziness and uncertainty to each measurement. Thus, the more polls you look at — whether in a graphic like the one above or a listing of questions using different language to ask about the same issue — the clearer the picture becomes. With polling, more is better.

Has there ever been a poll about whether highly trumpeted poll results affect views? When I think about it, my views of the President are skewed by these results, even though I am a strong supporter. I guess my question is related to the physics issue of whether in watching an experiment, it changes.

Oh – great and informative blog. I just want the truth from polls, if that is even possible. It is intersting that in the recent NBC?WSJ poll, I could find some of the methodoly on wsj.com, but not nbc. Such as the breakdown of sex. They said though that the margin is different for the subgroups in the poll, but didn’t show what the margin is. http://online.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/poll20060315.pdf

Baldy,

The German pollster, Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann, wrote a fairly authoritative work The Spiral of Silence on the use of public opinion polls as a form of social control. The reoccurring theme of eroding poll numbers picked up by potential respondents makes it less likely that those individuals responded in the affirmative to the Presidential approval item. In other words, most people are afraid of being the loner so they produce a socially desirable answer instead.

Bush at 33: The ‘I’ word

‘Honesty had been the single trait most closely associated with Bush, but in the current survey “incompetent” is the descriptor used most frequently …’

ouch…

While we’re talking about how poll results and news coverage and comparing across survey houses, let me mention a point made by Charles Franklin a couple months back.

Franklin made an interesting observation about how the frequency of polling by different organizations changes the coverage. Suppose Organization A polls every two months. Suppose Organization B polls every two weeks. Suppose a President’s approval number is dropping a point a week.

By the time Organization A has a second poll to report a trend, the approval ratings has dropped eight points. A story at the same time from Organization B will show a drop of only two points since the last poll. One drop is dramatic, and its coverage will reflect that. One drop is less dramatic, and will most likely reflect that as well. This is another case where knowledge of what others are doing, especially for the oganizations that poll less often, should have an effect on how polling results are covered.

As for whether what others think affects political judgments, Diana Mutz has written an excellent book called Impersonal Influence that addresses this topic in depth.

You know when Kurtz grumbled, “they give the collective impression that Bush is sinking week to week”?

Well, it seems to me the polls give that impression because Bush really *is* sinking week to week. Based on the data, what collective impression would Kurtz think is more accurate?

Appropos, I suppose, of not very much, I need to get this off my chest. This morning I was watching Greg someone, a talking face on Fox News, describing a new poll. He was pointing to a graphic which showed that 50+% of the respondants thought Bush was a lame duck President. Now, I recall a number of news stories over the past month talking about Bush being a lame duck President (Google for Bush+lame duck yields over 1.3 million hits). Given that the average person is busy living life and making a living, and is not a news junkie, and gets his slant on national issues from t.v., the local newspaper and the radio, he would come away with at least the vague impression that Bush is a lame duck President just by the passing references from all the media. So now you run a poll with that question in it and the guy says yeah, he’s a lame duck. Therefore, the poll doesn’t really test his knowledge or concern about that fact but, rather, the success of the media in pushing the meme. And, of course, it’s the same with tens of other memes over the past 5 years concerning Bush, his Presidency, the war, etc. The media beats the drum and then takes a poll to see how successful they’ve been, and then uses the positive aspects (from their standpoint) to produce more stories that say, “See, we were right and we do so report factually”. I can see why the President ignores polls. They really don’t have much to do with him.

Gotta give Kurtz credit for finding a way to spin decreasing approval ratings for Bush. It’s pretty impressive how persistent bias can be.

The graph seems to give evidence to the claim I made earlier: CBS has consistently carried the lowest numbers for Bush since 2005.

Let’s expose the Fakes, Phonies and Frauds.

1- Gallup Poll

Polling Methodology: Adults\Nationwide

Nationwide could mean California, Utah and New York.

Let me see if I could come up with results of Presidential Approval, without doing all the hard work involved.

Hey, let’s ask the Great Karnak:

NATIONWIDE

California 70% Poor 30% Good

Nebraska 55% Poor 45% Good

New York 70% Poor 30% Good

Poor 65%

Good 35%

ADULTS \ NON – REGISTERED (AKA “The man on the street”)

Let’s pose a few questions to this enlightened group. Let’s use 100 as the number polled.

Results

· Name Bill Clintons Vice President ——————– 80 Huh? 20 Hillary

· Name the current Vice President ——————– 90 Huh? 10 Correct

· How many members on the Supreme Court ———- 100 Huh? 0- Zippo

I believe it is your duty, as is mine to expose this Left Wing CBS\Gallup USA\Gallup

They poison the Well.

Furthermore. Did you ever notice how Left Wing Publications support Republican candidates, to show how unbiased they are?

Well those chosen have to be favored by at least 70 points. Newsday threw their support recently to Peter King.

This is another practice that should be written about.