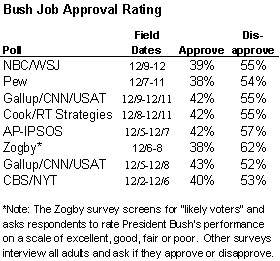

Yesterday saw releases of two new national surveys by the Pew Research Center (report, questionnaire, tables) and NBC/Wall Street Journal (full results & coverage by WSJ and MSNBC). Combined with a new Zogby survey released on Monday, we now have eight conventional telephone surveys conducted in December. Although seven of eight show a higher approval rating for President Bush, the three most recent releases all show Bush’s job rating under 40% and indicate smaller increases since November than the other four. As the field dates largely overlapped, the timing of the polls does not appear to explain difference.

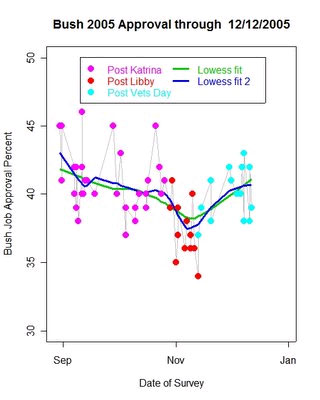

As usual the best way to consider the trend is to see these results plotted graphically, and once again Prof. Charles Franklin’s updated graphic provides the most coherent view:

The regression lines that Franklin plots through the data take into account the “house effects” that make Bush’s job rating typically run a little higher on some polls and a little lower on others. He explains those lines better than I can, and his analysis is worth reading in full. However, here is Franklin’s bottom line:

[T]here is reason to wonder if the significant rise we’ve seen since Veterans day has now reached a plateau, at least for the moment…approval continues to be significantly higher than the low-points before Veterans Day, but there is at least a reasonable doubt that it is continuing up at the rate it has for the past 3-4 weeks.

Also as usual, the Pew Research Center analysis goes into great depth on Iraq and a variety of other issues, including graphical views of the data that are well worth the click. On Iraq, the Pew Center sees more continuity than change:

[F]undamental public attitudes toward the war have not been changed in either direction by the clashing points of view. Pew’s latest national survey shows that the public continues to be evenly divided about whether to withdraw U.S. forces as soon as possible or keep them in Iraq until the country is stabilized, as well as over the decision to take military action in Iraq.

The most interesting finding comes from the way Pew combined results from questions that look into prospective policy regarding Iraq. As noted here previously, questions on what the U.S. should do next in Iraq yield highly inconsistent results across surveys. The new Pew analysis shows why. They found the nation remains divided on a question tracked since the beginning of the war: Whether the US should “should keep military troops in Iraq until the situation has stabilized” (49%) or “bring its troops home as soon as possible” (46%). However, they added a follow-up question on the recent survey, asking those who want to bring the troops home whether they favor an immediate or gradual return. They also looked at whether those who want to keep troops also want to “set a timetable for when troops will be withdrawn.” Their finding:

The roughly even division in the public over whether to keep troops in Iraq obscures a more complicated set of opinions about what to do next. Most of those who want to bring troops home “as soon as possible” apparently do not mean “now,” and not everyone who wants the U.S. to stay in Iraq is opposed to setting a timetable for withdrawal.

Of those who support bringing the troops home, most favor a gradual withdrawal over the next one to two years rather than an abrupt departure. Even among liberal Democrats, 66% of whom favor disengagement, most believe this withdrawal should be gradual (40% favor gradual withdrawal, 24% think it should occur immediately). Within every partisan group across the spectrum, support for bringing troops home is more likely to mean gradual rather than immediate withdrawal.

See the report for complete data and question wording.

The question I would like to pose is, “how stable are the categories of immediate, gradual, multi-year, eventual, or never withdrawal?” In other words, iss the public beginning to set deadlines in their own minds, or is opinion still fluid on this matter?

Mark,

This is a good chance to tie this thread on approval to the “Strategy for Victory” thread.

Some time ago (1996), Eric Larson at the Rand Corporation showed that the stakes of a military intervention and the prospects for success are key factors conditioning opinion.

He also analyzed the question of whether the public comes to prefer withdrawal, escalation, or some other option as it becomes frustrated with continuing casualties. Reviewing (mostly) Mueller’s data from Korea and Vietnam, his conclusion will surprise no one who sees the American public as consistently moderate (centrist)in its views: the percentage choosing “escalate” or “withdraw” never becomes anything close to a majority. Rather, when offered, the options of “orderly withdrawal” or when our POW’s have come home, or some other contingent option, usually prevails in the plurality.

Now, some of this is question effects, and that seems to be the case with recent surveys on Iraq. Asking if we should not withdraw “until the situation stabilizes” has two subtle effects. 1. the word “until” implies that it might (will?) indeed stabilize…which probably biases upward somewhat; 2. since “stabilizing” Iraq is pretty much our objective at this point, it’s hard to see how this sort of item is not simply yet another “support or oppose” the war question. The problems Berinsky points to come back here.

Anyhow, for all the evidence on commitment/withdrawal, as well as Larson’s early argument about stakes and prospects for success, see this free chapter:

http://www.rand.org/publications/MR/MR726/MR726.chap3.pdf

“Dead cat bounce” would describe the movement better. The term comes from Wall Street, where it compares the small bounce that a rapidly falling stock gets when it hits a bottom before falling again. The comparison involves a hypothetical cat falling from a skyscraper and bouncing a few inches off the pavement – meaning “anything will bounce a little bit”. To many readers, the comparison will seem apt, and is more marketable than the cryptic “bump-up stall”.

Thanks for the great analysis!

You’re right Camilo Wilson!